Community & Trends

December guest column

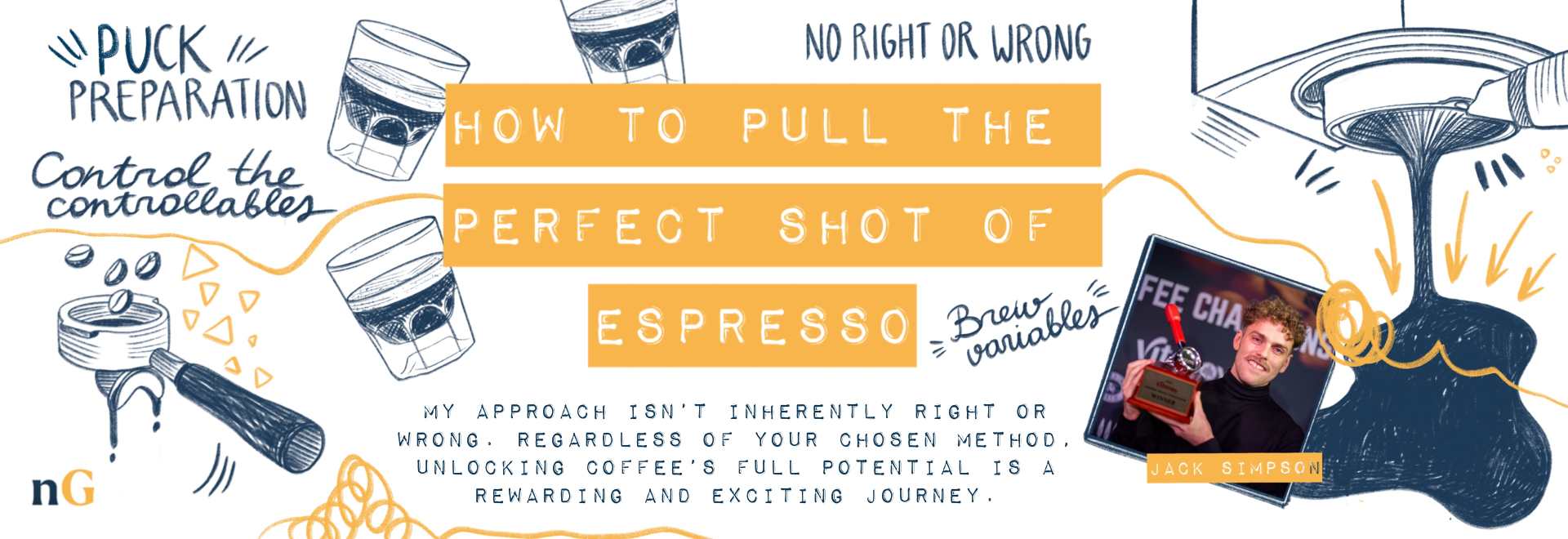

Ever wondered how to pull the perfect shot of espresso? Australian Barista Champion Jack Simpson gives us his step-by-step approach

Over the last eleven years of being a barista, pulling the “perfect espresso” has been a target I've always been chasing.

Whether dialling in the single origin in the morning before the first customer walks in the door or working with a lot of coffee that I'm using for competition – I tell myself that there is a “perfect” expression for this coffee…

Read moreNovember guest column

South African Barista Champion, Winston Thomas, talks about life after the lights go down on the competition stage.

As a kid, I often wondered what my favourite sports players did when they “retired from the game.” Our Springbok Rugby World Cup winning team recently completed their country-wide trophy tour and I’m sure a few of them will be hanging up their boots soon. It’s always sad to see them go.

I was on a local TV show a couple of years ago and…

Read moreOctober guest column

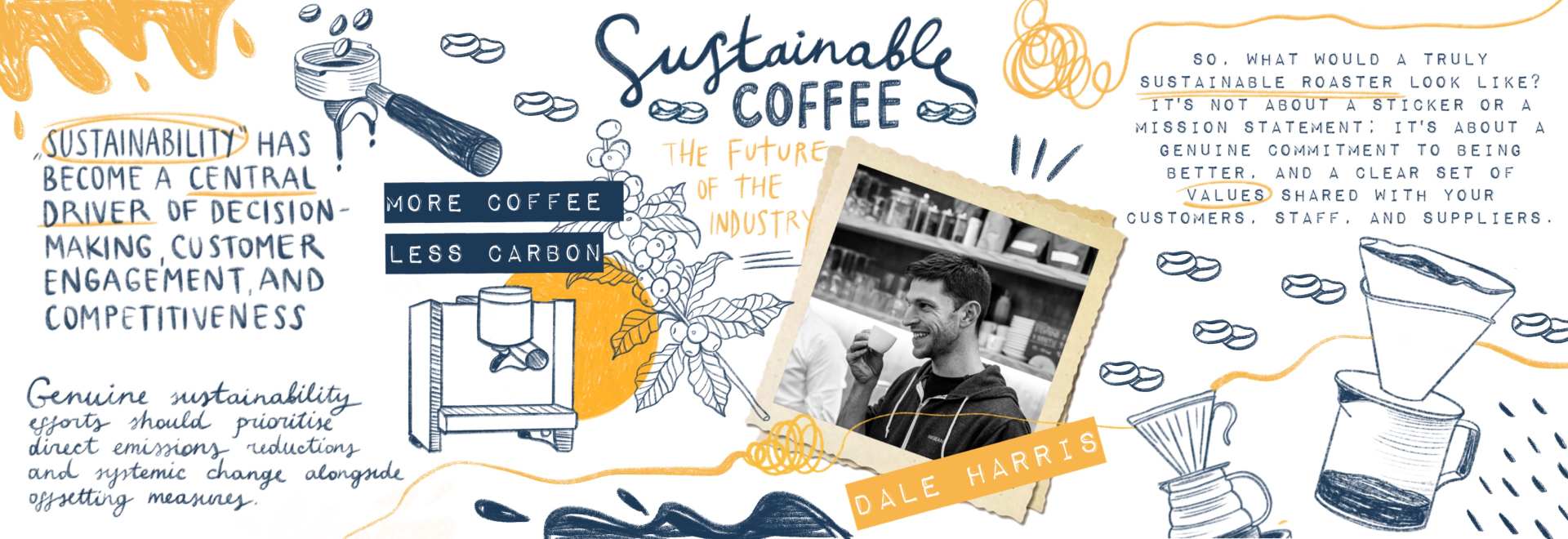

The coffee industry has some big challenges to face. Dale Harris talks about what role coffee roasters have, and dreams of a way forward.

For the greater part of specialty coffee's formative years, conversations around sustainability were tied to ethical purchasing. We dissected the merits and shortcomings of Fairtrade, extolled the virtues of direct trade, and focussed on a moral high ground of paying more per pound.

It was an acknowledgement of the flaws within the C-market, where prices often dipped below production…

Read moreSeptember guest column

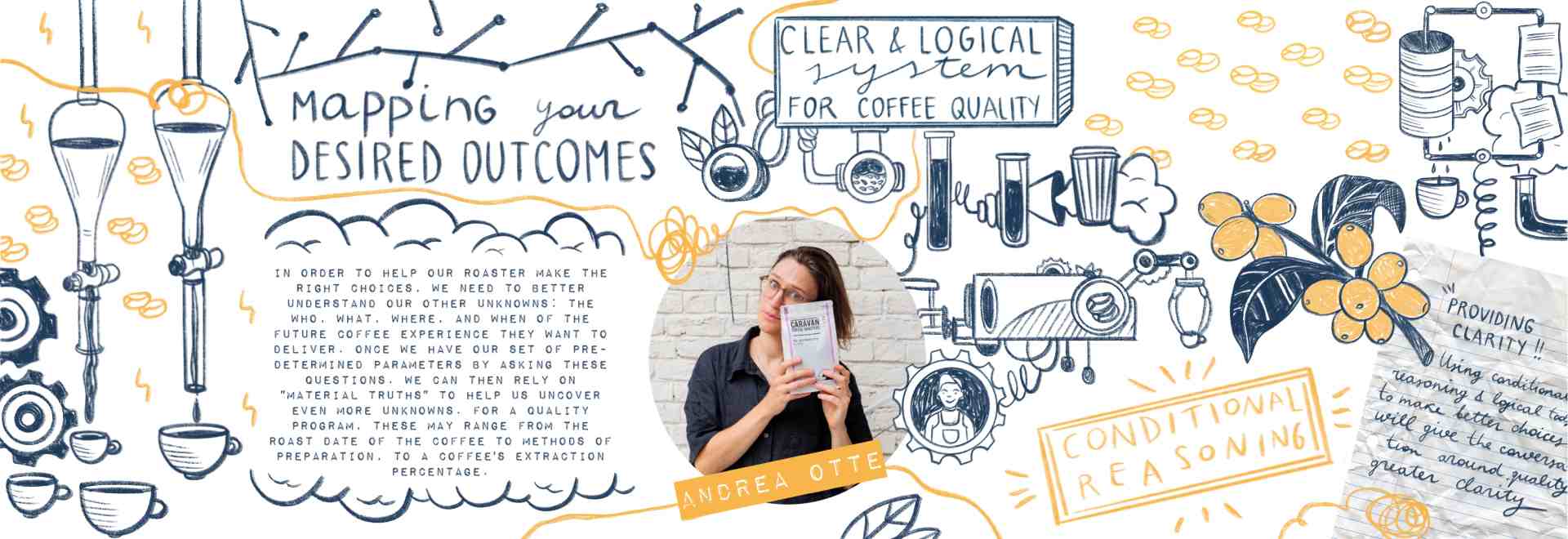

Head of coffee at Caravan Coffee Roasters, Andrea Otte, talks about her approach to creating a coffee quality program.

Ask a handful of people who work in the coffee industry to define “quality”, and you’re likely to get a different answer every time.

As the specialty coffee industry changes and many companies expand from small start-ups to multi-site enterprises, it can be difficult to locate where the concept of quality, or a quality control system, should fit into a growing business…

Read moreAugust guest column

Founder and CEO of WatchHouse, Roland Horne, tells us about his personal and professional experiences growing a specialty coffee company

In September 2014, I embarked on a journey into the industry, driven by my frustration as a disillusioned retail consumer. It wasn’t limited to coffee; rather, it encompassed my belief in redefining the retail experience in a truly authentic manner.

My travels to Australia, Japan, and South Korea further illuminated the stark contrast in retail authenticity back in the UK…

Read moreJuly guest column

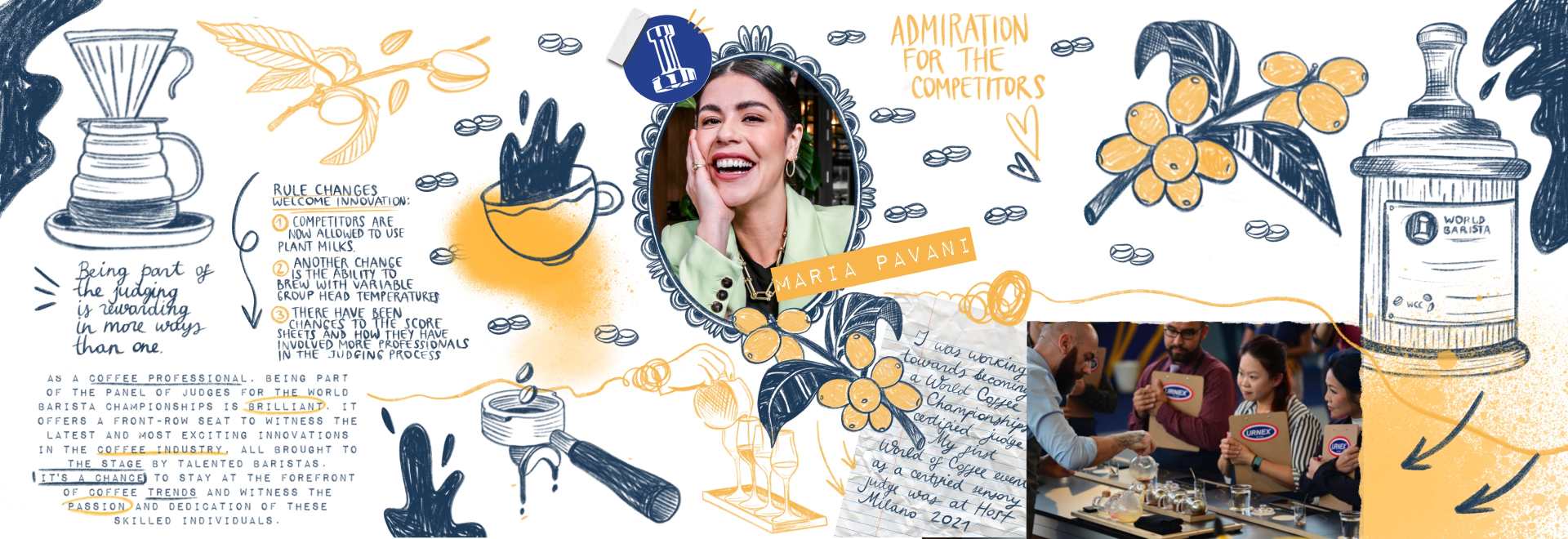

Maria Pavani gives her unique insight into the world of coffee competitions as a WCC-certified judge

I still remember when I started working in the coffee industry.

One of the highlights of being part of the specialty coffee community was following the World of Coffee shows and watching the World Barista Championships – where over 50 of the finest baristas in the world have 15 minutes to prepare four espressos, four milk beverages and four signature drinks, before presenting them to sensory and technical judges…

Read moreJune guest column

The founder of Redemption Roasters, Max Dubiel, shares his story of beginning a social impact specialty coffee company.

When we started Redemption Roasters seven years ago, our goal was to create a specialty coffee brand that went beyond exceptional coffee. Since then, it’s become evident that the way we talk about social impact in the coffee industry has changed.

Traditionally, impact in specialty coffee was primarily focused on ensuring fair wages and working conditions for farmers at the origin of coffee production. Think of the Fairtrade organisation, UTZ-certified and Rainforest Alliance-certified coffee…

Read moreMay guest column

World Brewers Cup Champion 2018, Emi Fukahori, offers her advice on how to approach coffee competitions and how to keep a cool head in front of the judges.

Competing is one of the best ways to grow as a coffee professional and as an individual. But growth comes with putting yourself outside of your comfort zone – and that’s exactly what competitions do.

Since they started, we have witnessed skilful baristas take to the stage showcasing innovations within specialty coffee. Only one person can win first place…

Read morePrevious Articles

Research & Development

Community & Trends

Design & Technology

Featured

Community & Trends

Community & Trends

Sustainability & Supply Chain

Community & Trends

Community & Trends

Community & Trends

Research & Development

Research & Development

Community & Trends

Sustainability & Supply Chain

Research & Development

Community & Trends