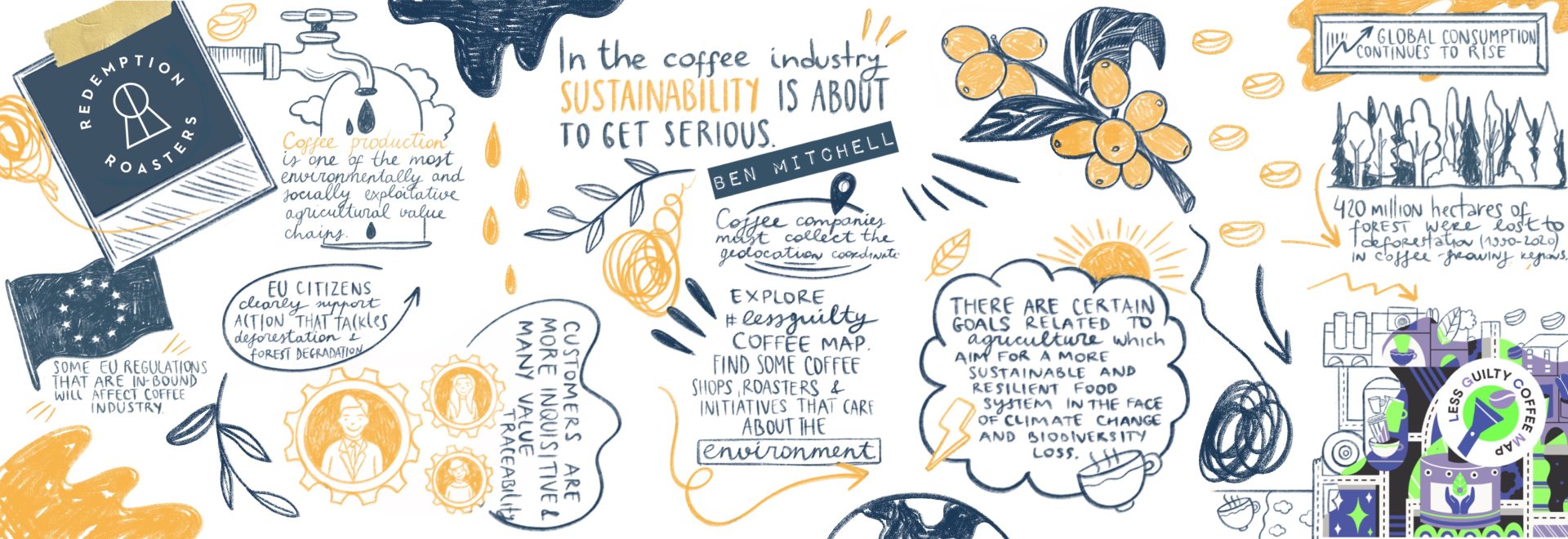

In the coffee industry, sustainability is about to get serious

Former café owner and senior manager at Redemption Roasters, Ben Mitchell, discusses why a new wave of regulations and changing consumer behaviour are about to shake up the coffee industry forever.

During my eight years working in coffee, sustainability has always been a part of the conversation.

But while our industry has flirted with ethical and sustainable business practices for some time, there are incoming rules and regulations that companies are going to have to take much more seriously.

As is well known by now, coffee production is one of the most environmentally and socially exploitative agricultural value chains, with massive monocrop production diminishing biodiversity and depleting soil nutrients, leading to the clearing of our forests as producers search for fresh soil. Processing methods, such as wet-milling, exhaust precious water resources, and volatile market prices leave producers in uncertainty, often being paid under $3 a day.

All the while, global consumption continues to rise. The International Coffee Organisation estimates that growing demand for coffee has led to a 60% increase in production over the last thirty years – a growing strain on our planet and its resources with each year that passes.

During the same period, some 420 million hectares of forest – an area larger than the EU – were lost to deforestation between 1990 and 2020, predominantly in coffee-growing regions.

Of course, coffee is not the sole contributor to the loss of our forests, but it is certainly part of a depletive agricultural network. As consumption continues to rise, a sustainable solution must emerge.

It is about time, then, that mandatory rules are introduced that hold businesses to account; pushing sustainability standards beyond the voluntary and often evaded rules that have allowed companies to stamp “fair trade” on their packaging.

The role of regulations

First, some EU regulations that are in-bound will affect our industry. And then I will discuss how that looks from where I come from, which is working in coffee shops.

The European Green Deal lays out three core targets: to have zero net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050; to decouple economic growth from resource use; and to have no person or place left behind.

Within this, there are certain goals related to agriculture which aim for a more sustainable and resilient food system in the face of climate change and biodiversity loss. An example of this in practice is an initiative that will provide EU citizens with a guarantee that the products they consume on the EU market do not contribute to global deforestation.

The regulation presides over a number of commodities, with coffee named specifically. Mandatory due diligence rules will be imposed on any of the commodities outlined, ensuring only those products deemed deforestation-free are allowed on the EU market.

As a part of this, coffee companies must collect the geolocation coordinates of the coffee-producing farm to ensure that coffee has not been sourced from deforested or degraded land.

Companies must log the number of producers working on each lot, the quantity and quality of the coffee beans, yield projections, and each time the beans change owner along the supply chain, gathering solid indicators and data at each step.

No small task, as a typical coffee supply chain includes at least 11 actors, from farms, co-ops, and importers to exporters, roasters, distributors, and coffee shops.

Logging this data will require financial investment and possible restructuring or capacity building – for example, as digital geotagging is incorporated into processes.

Our producers are faced with higher operational costs, more paperwork, national auditing structures that may not yet be established, and fierce competition from larger, more organised producers who have better compliance capacity.

The concern is for those without the resources to adhere to a mandatory reporting framework, who could be excluded from the EU market.

Shifting consumer behaviour

Meanwhile, consumer behaviour has started to shift. The Open Public Consultation for the Regulation for deforestation-free products gathered more than 1.2 million responses, the second most popular in EU history. EU citizens clearly support action that tackles deforestation and forest degradation.

This mindset is certainly something I have noticed while serving coffee. Customers are more inquisitive, and many value traceability. Forty-three percent of all coffee consumers state that they are influenced by “ethical, environmentally friendly, or socially responsible coffee options”.

But is 43% that much when the climate crisis is our single biggest existential threat right now, and coffee continues to be one of the most socially exploitative commodities?

It is fulfilling to have a conversation with a customer that understands the value of the cup I have handed to them, but it doesn’t ease the fact that the UK’s most popular coffee company also ranked lowest in Ethical Consumer’s survey of coffee companies.

What’s more, when reviewing some of my favourite coffee spots on Heylo’s Coffee’s Less Guilty Map, it is clear that customers – even those who are visiting shops with sustainability at the forefront of their business – are struggling to accept the higher prices that come with a more ethical cup of coffee.

The mandatory changes that are coming have associated costs which must be paid for, and paid for from somewhere that isn’t the producer end.

There is a disconnect between the coffee we drink and the process it took for us to drink it. Retailers need to normalise charging more for a cup or bag of coffee by connecting consumers with the provenance of their purchase.

For those that perceive coffee as a necessary part of their day, it may be a shock that prices are going up. Large coffee companies have been able to trade in commodity coffee and offer a price which consumers can swallow down without complaint. But that system is based on an environmentally and socially extractive value chain.

If companies are putting in money and work to abide by reporting frameworks and other sustainability regulations at the producer end, actors at the retailer end must work to shift that perception, connect consumers to the true value of their drink, and charge more for their coffee to pay their suppliers and producers a fair price.

Price increases must be managed with careful communications, but the message does need to get out: Those that farm the land to produce your coffee, and the land that they farm, are no longer able to take the hit. More goes into a cup of coffee than the two minutes that customers see. Cherish that coffee, savour it as a luxury, and feel thankful for the many hands that it has had to pass through in order for you to be taking that delicious sip.

One of my favourite coffee events was led by the roasters we worked with (Cuppers Choice). My old shop had opened back up after Covid with an all-Rwandan line-up. For the event, we cupped a bunch of coffees and then video-called one of the producers in Rwanda. It brought the supply chain to life, and you could see that resonating with everyone there.

It was a hugely gratifying event, bringing a greater understanding of the whole value chain to those who before had only considered the end product. But we did also sell a lot of coffee that day. The point being that the two can work in tandem – it just helps for there to be clarity about where the customers’ money is going.

It seems to have been a long time coming, with words like “exploitation” and “sustainability” knocking around the industry since I entered it. For all actors along the coffee supply chain, now is the time to take note of the imminent, mandatory changes; and to begin adapting and developing appropriate strategies that achieve financial and sustainability success.