The art of reducing astringency in coffee

Benedict Smith speaks with the Coffee Board of India’s quality specialist, Dr Ramya Mohan, about how baristas can harness the power of science to tackle astringent cups of coffee.

If you’ve bitten an unripe banana and noticed that your mouth feels dry, it’s likely you’re experiencing astringency – a harsh, tactile sensation that decreases salivary lubrication and causes a papery dryness on the tongue.

Although most don’t go looking for it, astringency can be found in a number of places, including cranberries, red wine, green tea, and pomegranate pulp. However, one of the most common sources of astringency is coffee.

Dr Ramya Mohan is a coffee quality specialist for the Coffee Board of India. She explains that while more detailed studies are required, scientists can pinpoint certain compounds that are responsible for astringent cups of coffee.

“The polyphenols and tannins in coffee contribute to astringency,” she says, “along with organic acids, such as malic and citric acids. It is also closely related to pH, in the sense that astringency is generally stronger when pH is lower.”

When drinking astringent coffee, it is these tannins and polyphenols that bind with salivary proteins, reduce oral lubrication, and increase oral friction – hence the dry sensation.

“Recent studies have demonstrated that astringency is a trigeminal sensation that involves the activation of G protein-coupled signalling by phenolic compounds,” Dr Ramya adds.

What gives rise to astringency?

It’s widely agreed among coffee consumers that astringency is an unwanted sensation. Not only does it produce an unpleasant mouthfeel, it can also mask many of the coffee’s distinct and subtle characteristics.

However, the first step to removing astringency is identifying precisely where it stems from.

Dr Ramya explains that the compounds responsible for astringent coffee can be produced during four different stages: cherry maturation, processing, roasting, and brewing.

For example, immature coffee beans are generally more astringent than overripe cherries, while over-roasting coffee often gives rise to higher astringency than under-roasting.

Certain “experimental” processing methods have also been shown to increase astringency due to the formation of ethanol and acetone related acetic compounds. “These may act as a dehydrating agent and cause astringency,” Dr Ramya says.

However, for many it is the brewing stage at which astringency occurs the most. This is because it is this point where a lot can go wrong, particularly for those who are inexperienced.

“An over extracted coffee has a greater probability of being astringent and bitter,” Dr Ramya explains. “This can be attributed to improper grind size (finer than the ideal grind size for a particular brewing method), high water temperature, water quality, long contact time, clogging and channelling during extraction, intense agitation, or improperly applied pressure.”

How to reduce astringency at the brewing stage

With so many factors at play, avoiding astringent cups of coffee can seem like an impossible task. But while home baristas can play around with different factors over a long period to find the perfect variables, time is often more of a concern for coffee shop owners looking to retain customers.

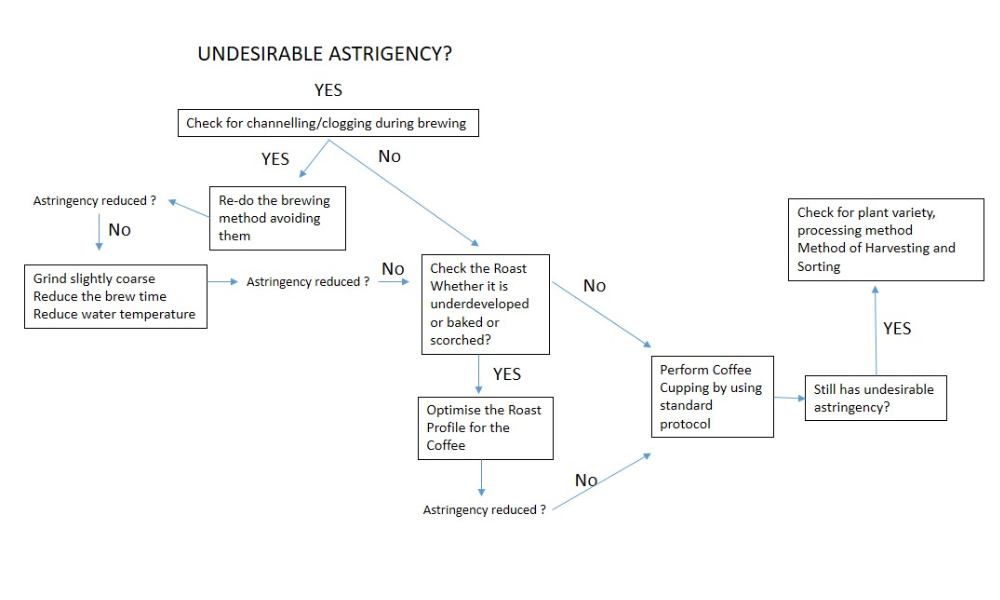

Fortunately, Dr Ramya and her team at the Coffee Board of India have devised a simple flowchart that breaks down how baristas can use astringency as a guide to land on the perfect cup of coffee.

It starts by checking for channelling and clogging, before moving along to suggestions of a coarser grind size, shorter brewing time, and lower water temperature.

If changing these variables doesn’t reduce astringency, the flowchart suggests looking into the roast itself and performing a coffee cupping using the SCA standard protocol.

If none of this works, the final option according to the flowchart, is to look into harvesting, sorting, and processing methods, as well as finding out more about the coffee’s variety or species. For example, robusta is relatively more astringent than arabica.

However, Dr Ramya explains that contrary to popular belief, the goal when brewing coffee shouldn’t necessarily be to completely remove astringency.

“The aim for a good extraction is not to completely rule out the chemical compounds causing astringency,” she says, “but to obtain a perfect balance between acidity, sweetness, bitterness – and astringency as well. For example, in the case of wine, it is widely acknowledged that high-quality red wines have a balanced level of astringency.

“But in order to achieve that balance, it is important to obtain ideal extraction.”